Weaving the threads of my past

Interview with Peter Pleyer

Edited by Nicole Bradbury

#books #arnhem #solo #magazines #teachers #aids #berlin #newyork #weaving #healing #greif #ponderosa #bodywork #honouring #growing

Peter

Nitsan

It would be great if we would somehow move from your personal work, and see how it expanded in relation with the Berlin scene, because you also have worked as a curator and facilitator of various structures in the city. And also through multiple times.

Peter

I don't know how long you have been in Berlin, but there is also the curiosity of the beginner: you're coming into a scene that you think is somehow established, but it's not really, it's constantly evolving. And there are many scenes within the scenes, and there are many histories within the histories. I've been here 20 years. I came in December 2000. I have been through many involvements as a watcher, and then as a curator of Tanztage Berlin, and then since 2014 as an individual maker of solo work and group work. And the solo works and group works work parallel, one informs the other.

... there are many scenes within the scenes, and there are many histories within the histories.

Nitsan

Maybe we can then jump into your work with the HIV AIDS archives. How do the artists that work through those times relate to the current moment in which we're in?

Peter

This is a hard topic to start with, because it's very painful. We're talking a lot about loss of lives, but also of ideas. And we have to start with my dance education. The school I studied was called the “European Dance Development Center”, and it is a school that no longer exists. It was an offspring of the “School for New Dance Development” (SNDO) in Amsterdam. The offspring happened in 1989 when one of the directors thought that the education had already been built into very closed systems of school, and he really wanted to open it up into a more performative school. That was Aat Hougee, a Dutch man who co-founded SNDO in 1975. I came as a student to that new school in Arnhem in 1990. And the school was very open, had very different teaching formats, and had very different alternative formats of teaching choreography and technique. We didn't have any ballet, or any Cunningham, or any other conventional technical training. But all the training was done by the artists, the choreographers who would come to teach workshops. So we had continuous work for four years of daily practices and work in the studio. There was not one training that we would go through, but it was workshops of six weeks, seven weeks, eight weeks, where we would dive into one

technique, or where we dive into one idea about the body, linked always with the creative work of that artist. And it's been a total mind opener when we're talking about diversity. There's so many techniques, and ways of working on choreography and technique. This is important to understand that 70% of all the teachers were guest teachers. And most of them would come from the New York downtown arts community. And within that the AIDS crisis was really big in New York at that time. So a lot of teachers who would come would introduce methods of grief, or stories about people who were dying. There was a whole different understanding of urgency. It was very clear that a teacher would maybe not come back next year, because he might be dead. A very influential person in this respect was Yoshiko Chuma, a Japan born choreographer who has lived in New York since the early ‘70s. She invited me into a student-project that was travelling New York in the early ‘90s. And one of the teachers that she would bring to Arnhem was Harry Shepard. They travelled together to Arnhem by the plane from New York, and he had disclosed to Yoshiko that his T-cell rate was very low. And so he flew to Arnhem, and he got sick in Arnhem, and he died in a hospital in Arnhem within two weeks. Shocking. I grew up in a city where I was active in an AIDS-help Centre in the late ‘80s. So I was one of the students who would not be afraid of touch – I knew the way the infection would transmit – so I was taking care of Harry during the time.

… the AIDS crisis was really big in New York at that time. So teachers who came would introduce methods of grief, or stories about people who were dying.

There was a whole different understanding of urgency.

Sasha

Am I right that the majority of the material that you are dealing with is this interpersonal transmission from artist to artist, from teacher to colleague? Are you interested in any other kinds of materials, or archival documents present in your work?

Peter

An initial story is me being asked as a student in 1991 to make my first solo work, and I had no idea what to make. I was kind of blank, so I locked myself into the newly established video archive of EDDC and I watched every single tape of that archive.

And it was really incredible – this was a whole new world: seeing other people, seeing work that has been done in the last years. Meeting people that I had never seen or heard of. It was an incredible teaching – just to be in the archive for a week and watch everything. And one of the tapes that I found, I'm still using in my teaching, which is called Variety Show. It's duets of all the teachers that were teaching in the summer of 1988, in SNDO. And it's just an incredible document of teaching methods and aesthetics in one tape. So this video material in the ‘90s was starting to become important. But also in the beginning of the 90s was the start of dance as a research field. Susan Leigh Foster started her first Ph. D programme for dance history and research. And so there was a growing interest in researching and books about dance. One of my colleagues from Arnhem, Karen Schaffman, would be one of the first students to do a PhD in University of Riverside. I asked her to send me all her reading lists, and then I started this search for these books. The internet was young – it was really difficult to find books on dance and dance history. And it was really difficult and expensive to get them. So in the late ‘90s, coming to Berlin, I really made a lot of effort to hunt for books. And in 2005, Tanzfabrik invited me to make a solo, and the only solo I wanted to make was one where I worked with my acquired library. At that time, I had about 60 dance books. I brought them into the studio in Möckernstraße for four weeks, and I lived,and read, and rolled, and danced with the books. And out of this came a solo called Choreographing Books, and I performed it for more then 10 years. I brought that piece to the places I taught: in HZT Berlin and the MA in Arnhem, and many other schools and theatres. And out of this, also some other teaching usually emerges.

An initial story is me being asked as a student in 1991 to make my first solo work, and I had no idea what to make. I was kind of blank, so I locked myself into the newly established video archive of EDDC and I watched every single tape of that archive.

And it was really incredible – this was a whole new world: seeing other people, seeing work that has been done in the last years. Meeting people that I had never seen or heard of. It was an incredible teaching – just to be in the archive for a week and watch everything. And one of the tapes that I found, I'm still using in my teaching, which is called Variety Show. It's duets of all the teachers that were teaching in the summer of 1988, in SNDO. And it's just an incredible document of teaching methods and aesthetics in one tape. So this video material in the ‘90s was starting to become important. But also in the beginning of the 90s was the start of dance as a research field. Susan Leigh Foster started her first Ph. D programme for dance history and research. And so there was a growing interest in researching and books about dance. One of my colleagues from Arnhem, Karen Schaffman, would be one of the first students to do a PhD in University of Riverside. I asked her to send me all her reading lists, and then I started this search for these books. The internet was young – it was really difficult to find books on dance and dance history. And it was really difficult and expensive to get them. So in the late ‘90s, coming to Berlin, I really made a lot of effort to hunt for books. And in 2005, Tanzfabrik invited me to make a solo, and the only solo I wanted to make was one where I worked with my acquired library. At that time, I had about 60 dance books. I brought them into the studio in Möckernstraße for four weeks, and I lived,and read, and rolled, and danced with the books. And out of this came a solo called Choreographing Books, and I performed it for more then 10 years. I brought that piece to the places I taught: in HZT Berlin and the MA in Arnhem, and many other schools and theatres. And out of this, also some other teaching usually emerges.

Especially because it looks at techniques, and it looks at artworks of people that are not widely seen or known, for example, it was in Contact Quarterly where Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen would publish her first articles on BMC.

And with magazines, because they're published again and again, they can be really quite accurate and current. So Contact Quarterly in the last 5-6-7 years has changed its content into publishing more articles and interviews by people of colour. And it's the same with the Movement Research Performance Journal. Over time I have

collected the full back issue set of these magazines. Usually, when I start a project, I bring all of the books, the magazines, the videos, and I talk about my experience, but then I let people find their way in it, and through it, articulate their interest, almost finding their own way into the past.

… the only solo I wanted to make was one where I worked with my acquired library. At that time, I had about 60 dance books.

Nitsan

This idea of remembering is extremely important, as a way of mentioning the names. Susan Leigh Foster is extremely important in our conversation, as well as all the threads, you've been speaking about. I think magazines... they are lighter when you think of materiality, because they're not going through so much editing as well.

Peter

There can be a real big difference in editing, I think that the success of Contact Quarterly is because the two excellent editors, Nancy Stark Smith and Lisa Nelson, put a lot of work into editing. Each magazine has a different approach, the Movement Research Performance Journal is much more excessive – there's much more text... On the other hand, Martin Spangenberg’s initiation in Stockholm with his Swedish dance history is completely unedited; people could just contribute whatever they wanted to contribute at that time.

The interest in making a book on recent dance history of Berlin is always there. But it always fails on the immensity of people that are actually here doing something <...>

It's just hard to put a finger on.

Sasha

I saw it in Lake Studios. It's crazy...

Peter

I have it, but almost never look into it. Because it's so unedited.. Sometimes publishing everything that is contributed is worthwhile, but maybe sometimes not.

Nitsan

It also brings questions of improvisation choreography. How do you craft someone? How do you choose what is in and what is out? It's really choreography of words. And if Berlin has some kind of a book like that, of the dance archive, how is it right now? Or how was it a year, or two, or five ago?

I saw it in Lake Studios. It's crazy...

Peter

I have it, but almost never look into it. Because it's so unedited.. Sometimes publishing everything that is contributed is worthwhile, but maybe sometimes not.

Nitsan

It also brings questions of improvisation choreography. How do you craft someone? How do you choose what is in and what is out? It's really choreography of words. And if Berlin has some kind of a book like that, of the dance archive, how is it right now? Or how was it a year, or two, or five ago?

The interest in making a book on recent dance history of Berlin is always there. But it always fails on the immensity of people that are actually here doing something. It becomes quite a huge, multi-layered, multi-focused situation and it's really complicated and difficult. A lot of people don't want a certain telling, they want a bouquet of tellings. This is what I wanted in Tanztage, which is another archive. I curated Tanztage for seven years, and within my seven years we had the 20th edition. For the 20th edition, we reprinted all the programmes from the past 20 years. It was an incredible archive of plurality. There were people who had not made it, or who left Berlin, or who changed professions and other who are big now and had their first shows during Tanztage. But even these pathways are so diverse and mysterious. It's just hard to put a finger on. There is Tanznacht Berlin, an initiative of Tanzfabrik, and it used to be every two years. And for one of the editions in 2012 I worked together with Andrea Keiz and Arianne Hoffmann to create the oral dance histories room at uferstudios. Andrea Keiz used to work for Mime Centrum, so Andrea has filmed incredible amounts of dance performances in the 2000s and Arianne Hoffmann just came to Berlin after her studies in Los Angeles and really wanted to understand Berlin's dance scene. We conducted conversations beforehand with older protagonists from the Berlin dance community. Our system of doing these interviews was meeting someone for at least three hours and doing handicraft together during these three hours conversations. We would knit or crochet together. We would sit around a table, ask some questions, and then people would start talking. Our effort was to make it long, because to some points, you only come when you have set aside all the superficial things. For the installation in the room at Uferstudios we put up a lot of photos, and all the things we crocheted and on a big table extra wool and needles for visitors to work with. So you could get headphones and listen to the recorded conversations while you were doing something with your hands. People really spent a lot of time in this room. I'm sure there's still a lot of data in those <recordings>.

For Visible Undercurrent in 2014, I visited both archives of my former school (EDDC in Arnhem) which is unfortunately not taken care of – it's really a loss, and SNDO Amsterdam, they have an incredible archive that is very well taken care of, and the same woman is in charge who has been in charge since the late ‘80s. She knew immediately where things were, and she had knowledge of how it got there.

For Visible Undercurrent in 2014, I visited both archives of my former school (EDDC in Arnhem) which is unfortunately not taken care of – it's really a loss, and SNDO Amsterdam, they have an incredible archive that is very well taken care of, and the same woman is in charge who has been in charge since the late ‘80s. She knew immediately where things were, and she had knowledge of how it got there.

… these interviews was meeting someone for at least three hours and doing handicraft together during these three hours conversations.

How have you documented your work from recent years, and what do these documentations include? And maybe you can also link it to that archive of Amsterdam that you mentioned? What kind of material is considered? Is it scores, or mostly videos? What kind of documentation is useful for us to practice with, and what is stored?

Peter

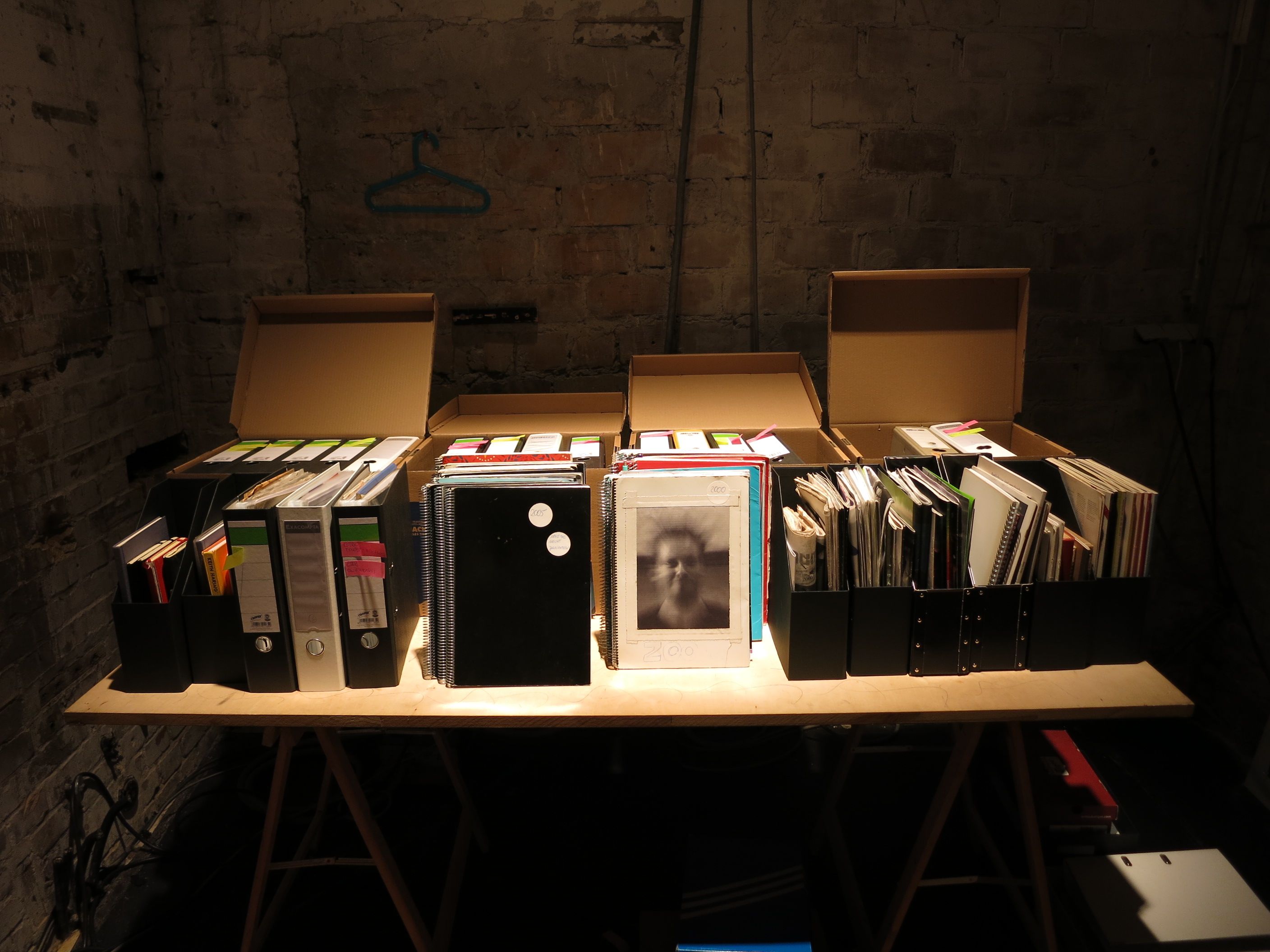

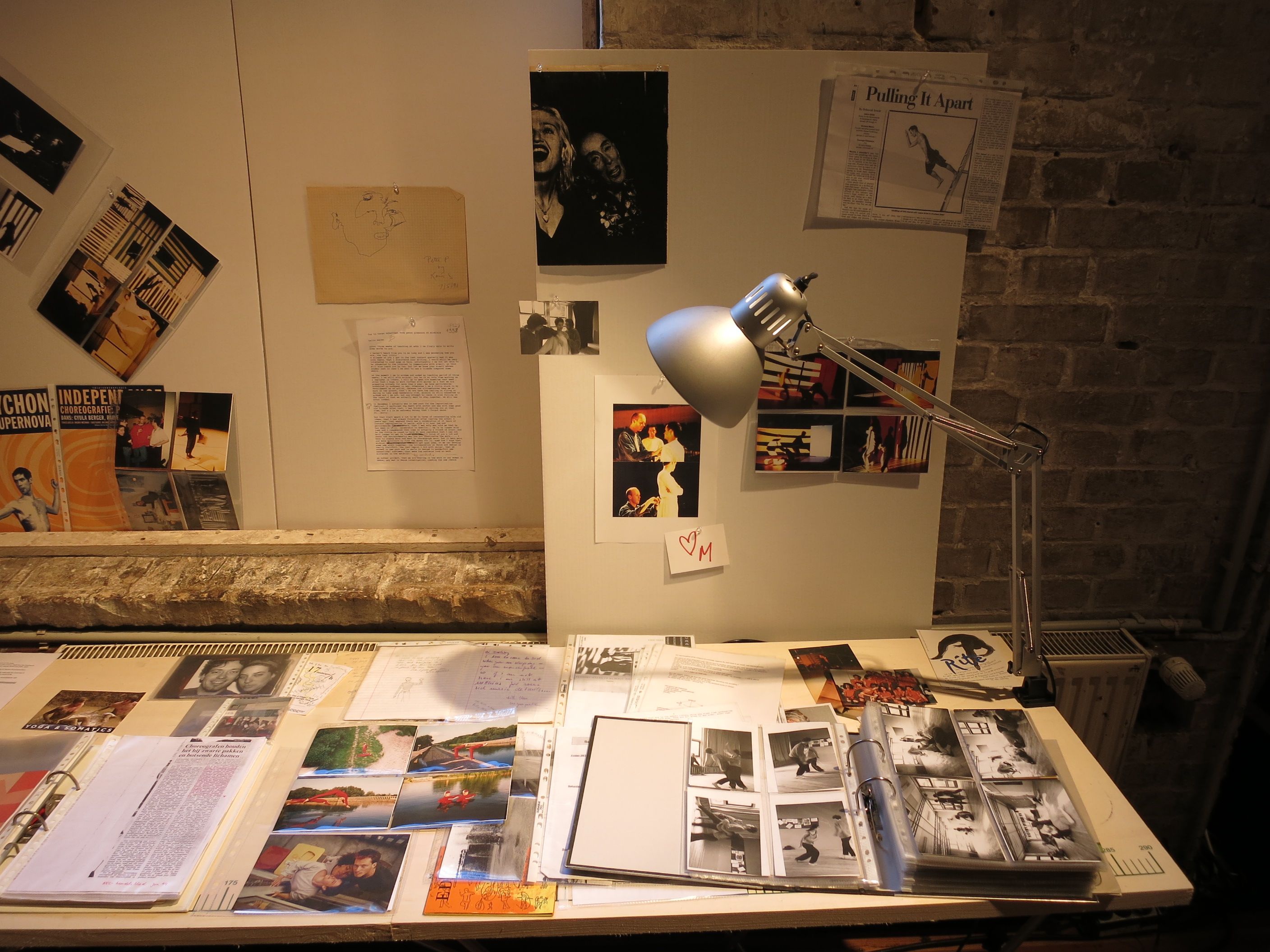

I do think any documentation is worth keeping for a while. But also, you need to find the time to revisit, clean up, bring in order, make some sense of it. That was the attempt for Choreographing Books. And for this other piece I did "p", which I also called "peter pleyer portfolio performance piece", Dock 11 gave me a room in Eden to just carry my boxes there and start sorting through. My archives were a big mess: after I make the project, I put it all together in a box, and store it. But to have the chance to actually look at it again, and put it in sections, or put it in order, or clean it up, maybe transcribe some of the scores, maybe transcribe some of the text that you have written holds a great chance. Documenting all programme texts and a lot of visual material from processes... it's too much. You need a really strong editing idea, and you need to find time. And when you haven't touched an archive or a box for four-five years, and you dive back in, there is a distance and things can make sense.. To have this opportunity to make this piece was really incredible. To look at everything and put it in a certain order.... So I don't have a system. My system is revisiting after a while.

Sasha

It sounds like a system for me. And I think that maybe it's the only possible system that we could have for something that is so diverse and unequal.

Sasha

It sounds like a system for me. And I think that maybe it's the only possible system that we could have for something that is so diverse and unequal.

Peter

This has good sides and bad sides. Some of the boxes are in order and they're put away. I'm not so interested in them anymore. Whereas with the chaotic boxes, I still have an interest. For the piece, I had all the documents on these tables in files, but also in mood boards. The performance was in the evenings, and during the day

… I don't have a system. My system is revisiting after a while.

audiences could just come and visit my archive. It interested people and for me it was a very successful project, but not very many people saw it so even that feels marginalized on that level. That's maybe why I still think that contemporary dance and then alternatives in contemporary dance are marginalised, because they never attract huge audiences. So a new project is to look at these solo works that I have, and to look at them and narrate them in prose. So I would make a written version of the solo works, that then would become a little catalogue to put it in a different medium, a different frame. I do believe that my work with the archive, my work with people dead or still alive, is quoting them or what I learned from them.

Speaking about contemporary dance, when it gets on stage, it's not so much public, and we get off stage to the idea of practical research... we're really getting into a niche where it is happening on the margins, even when we think it's not. And you're speaking about acknowledgement, and maybe other ways of transmitting that knowledge, that you're speaking now as a prose, or as other ways of mediation... in order to inform and to reach out...

Peter

It's both, and it's also clarifying my foundations. So if I talk about Diane Torr, a dancer, a teacher, a friend of mine, who died in 2017 of brain cancer, she's so relevant now. She was mainly teaching women how to be a "Man for a Day" – that was the title of her workshop. She was one of the first people in the drag king movement. It's very rare that somebody knows of her work. Paul B. Preciado, who now is very big on body politics and trans queer politics, the former identity Beatriz, their first contact with a male persona was in a workshop of Diane Torr in San Francisco hosted by Annie Sprinkle. So Beatriz took a workshop with Diane Torr, and that was one of the stepping stones for Paul. And I think it is important to keep referencing, keep bringing these stories and help people stay alive in a sense.

… my work with the archive, my work with people dead or still alive, is quoting them or what I learned from them.

Nitsan

There's so much in this, the messiness of the box, that of course that's where you're looking to find things.

Sasha

I have controversial thoughts in my mind, because in our description, we have this idea that Western European and North American lineages are very present. But now, 70% of the names that you are mentioning, I have no idea who these people are and I would wish to learn more. Speaking of accessibility of your profound and huge archive, I'm wondering, do you have an idea for what its destination is? Or maybe you will keep transferring this knowledge to your solo works?

Peter

One of the reasons I did Choreographing Books, was that increasingly I got questions like "Can we meet and can we go through your bookshelf?" Then we would have a coffee, and we would sit and talk and I would take some things out of the shelf. So these private meetings, to see what can be helpful – this is also a way of my teaching. When I'm asked to teach, I always travel with a suitcase of books. I can point people to what I think might be interesting for them to read. I try to feel what people can benefit from, and my interest in it is not fading. And then I think more of this growing archive, and it's something that people I work with carry on. For instance, Agnès Benoit, a French dance researcher, came to Berlin in 2006, saw my book piece, came to me after the show and said, "This is a really interesting piece, and can I give you my book to include?" And it was an interview book on improvisation called On the Edge. She conducted interviews with dance performers who use improvisation in performance. It's from the late ‘90s. And then she said, "All these books are not easily available, so I will start an online store for dance books". She started in Berlin to establish an online dance bookstore, which is called Books on the Move. She moved back to France about seven years ago, where she continues the bookstore in France. This bookstore is an incredible resource, and incredible archive. Then it's not my work, it's Agnes's work, but it came out of our exchange and out of Choreographing Books. Or Marcio Kerber Canabarro, a dancer that I’ve worked with for 10 years, is editing a series of online magazines called CARE WHERE? Zine. He does a lot of oral history, talking about people he met, people he is influenced by. So it's again not my archive, but it's a growing archive that helps people articulate.

One of the reasons I did Choreographing Books, was that increasingly I got questions like "Can we meet and can we go through your bookshelf?" Then we would have a coffee, and we would sit and talk and I would take some things out of the shelf. So these private meetings, to see what can be helpful – this is also a way of my teaching. When I'm asked to teach, I always travel with a suitcase of books. I can point people to what I think might be interesting for them to read. I try to feel what people can benefit from, and my interest in it is not fading. And then I think more of this growing archive, and it's something that people I work with carry on. For instance, Agnès Benoit, a French dance researcher, came to Berlin in 2006, saw my book piece, came to me after the show and said, "This is a really interesting piece, and can I give you my book to include?" And it was an interview book on improvisation called On the Edge. She conducted interviews with dance performers who use improvisation in performance. It's from the late ‘90s. And then she said, "All these books are not easily available, so I will start an online store for dance books". She started in Berlin to establish an online dance bookstore, which is called Books on the Move. She moved back to France about seven years ago, where she continues the bookstore in France. This bookstore is an incredible resource, and incredible archive. Then it's not my work, it's Agnes's work, but it came out of our exchange and out of Choreographing Books. Or Marcio Kerber Canabarro, a dancer that I’ve worked with for 10 years, is editing a series of online magazines called CARE WHERE? Zine. He does a lot of oral history, talking about people he met, people he is influenced by. So it's again not my archive, but it's a growing archive that helps people articulate.

Nitsan

It's interesting to think that the Berlin Tanzarchiv group is thinking about what an archive could be. I'm also thinking of the idea that we carry our archive with our body, and you're sharing your resources, archive, accomplices that you're working with and creating with. I'm also thinking of more makers like Netta Yerushalmy, who made Paramodernities, where scholars would speak on stage, bringing these archives/books/knowledge together with the dance, moving it and transforming it.

Peter

You're pointing to understanding dance on a broader scale, to have other assets, like interdisciplinary work in performances. In my solo work, it's more oral history or I have books and magazines on stage that I give to the audience. It's a very personal exchange, but my very first piece after I ended my education was with Eszter Gal in Budapest. We're improvisers, so we were just improvising together – the two of us. And everywhere we would go to perform New York, Paris, Budapest, or Amsterdam, wherever we went everybody in the audience was engaged, but they still saw the man and the woman and the love and the attraction. They all made these traditional narratives out of what we were doing. And we said, "Wait a minute, this is completely not what we're doing. I'm a gay men, Eszter is a straight woman. We're dealing

with very different things and aspects. We're dealing with formality, cross dressing, dance history, philosophy, literature, with who we are as people". So we made a piece where for an hour and fifteen minutes, we explained to the audience who we are, what we're doing, showing examples of videos, doing a short history lecture, reconstructing something that Trisha Brown had done, reconstructing early Contact Improvisation. And then we dressed in costumes, and we did ten minutes of our improvisational dance, and the audience was always very touched to get tools to read it in a very different way. I think it's brave and great to break the dichotomies; this is dance, and this is talking about dance. I think that's maybe part of the education, that if you're an artist, you're not fixed on a form or system.

… if you're an artist, you're not fixed on a form or system.

Moving Margins Chapter II

moving arti|facts from the margins of dance archives

into accessible scores and formats

Supported by the NATIONAL PERFORMANCE NETWORK

- STEPPING OUT, funded by the Federal Government

Commissioner for Culture and Media within the

framework of the initiative NEUSTART KULTUR.

Assistance Program for Dance.

artistic researches

Supported by the NATIONAL PERFORMANCE NETWORK

- STEPPING OUT, funded by the Federal Government

Commissioner for Culture and Media within the

framework of the initiative NEUSTART KULTUR.

Assistance Program for Dance.

© 2021 All rights reserved to Sasha Portyannikova, Nitsan Margaliot and the interviewees.