We believe too much in sensemaking

Interview with Jule Flierl

Edited by Nicole Bradbury

#valeska_gert #voice #archive #taste #sounddance #activist #western #contemporary #absurdity #tontanz #allyship #claiming #gesture #paradox

Jule

But I do think that what we call "contemporary art" and "contemporary dance", it's not about time, but it's about geography. And it is about the geography of the Western countries that are mainly European, US American. And I think that South Korea, Japan, and probably Israel (that is a claim that I would love to know your opinion about Nitsan ;) also play into this Western realm. But there's something about what counts as "being in the time" that is Western. And of course, we can have a whole discourse about what counts as Western. This is not my focus. My focus is basically to try to understand how the notion of "contemporary art" and "contemporary dance" always show how "contemporary others” are behind. And this is really interesting, because I'm part of the contemporary dance world.

The wall came down when I was eight, and my childhood was among these disoriented adults whose artistic work became irrelevant..

I went to dance school in Salzburg SEAD. The teachers were constantly saying "this is not contemporary enough". And also in meeting works from archives I feel repulsed by many of the works. I intellectually would like to empathise, but I do have taste, so it's a really interesting negotiation with taste and non taste, and where does taste come from? Where do my preferences come from? And I love to interrogate myself about my taste too – it's a really interesting conversation. That is also unsettling my own preferences as a certain history of becoming an artist and spectator myself.

Sasha

This resonates with me a lot. Sometimes I think that being a spectator is my practice of self psychoanalysis. When I like or dislike something, why? What makes me like or dislike it?

Jule

Exactly. If I see some pieces, and I think "Okay, so that's really fashionable". It's really interesting to think about "why?" And how does this satisfy me? In what way? What part of me does it satisfy? And where can I find interest and satisfaction in things that are completely anachronistic, but that doesn't mean they're not relevant. So I have a fascination for this interrogation of tastes, and to really question taste as a tool for decision making.

Sasha

This resonates with me a lot. Sometimes I think that being a spectator is my practice of self psychoanalysis. When I like or dislike something, why? What makes me like or dislike it?

Jule

Exactly. If I see some pieces, and I think "Okay, so that's really fashionable". It's really interesting to think about "why?" And how does this satisfy me? In what way? What part of me does it satisfy? And where can I find interest and satisfaction in things that are completely anachronistic, but that doesn't mean they're not relevant. So I have a fascination for this interrogation of tastes, and to really question taste as a tool for decision making.

...what we call "contemporary art" and "contemporary dance", it's not about time, but it's about geography. And it is about the geography of the Western countries that are mainly European, US American.

Nitsan

Taste brings me to the thought of intuition. Are our taste and intuition things that we come with or actually things that we learn? For me, intuition is something that I learned my whole life, so it's actually not my taste at all. It's completely what surrounds me, my culture... I see it in my conversations with my partner where I'm referencing race in such a specific way that it's as if I'm seeing Europe with American eyes. I didn't have it before. And now it's my intuition. It's my learned and lived experiences that are shaping me, and I think everybody somehow learns to have this taste or to have this intuition. It makes me connect to yesterday's conversation: Why is Butoh in the margins? Why was it not captured yet?

…. where can I find interest and satisfaction in things that are completely anachronistic, but that doesn't mean they're not relevant.

I don't know, in the 90s in Berlin, there was a huge Butoh scene here. I was more in contact with Butoh than with contemporary dance. If you talk to people from another generation that were active in the 1990’s, a lot of them were influenced by the practices of Yuko Kaseki and Minako Seiki, and Imre Thormann. In DOCK11 they still show a part of this generation of people involved with Butoh. It was like a fashion in Berlin that now seems quite outdated. But why? Just because the people who did it are older now?

Sasha

That's interesting, because in Moscow and St.Petersburg it was the same. The majority of my teachers practiced Butoh a lot, and it formed their practice as contemporary artists. I'm curious why it could be considered on the margins, because it's very honourable in the dance community that I came from. It's super interesting that in these transitional periods, you told the elder generation of artists – in the 90s in Berlin – there were many processes that were similar to the 90s in Russia.

Nitsan

You worked with various archives, but which specific archive would you like to discuss in relation to alternative approaches to the archive? I think all your projects are kind of dealing with this alternative way that you're transforming them.

Jule

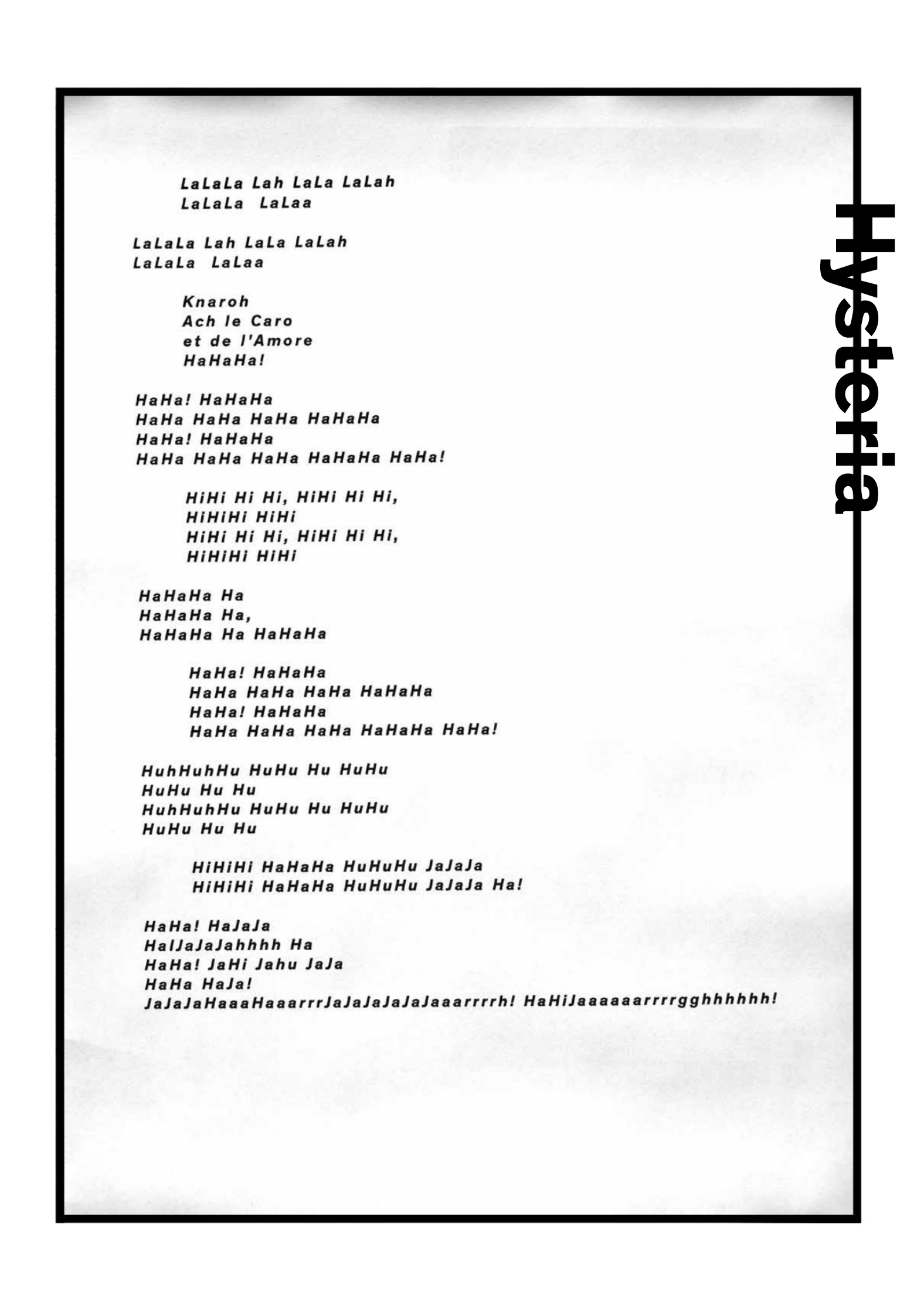

For years in my practice, the concern was the voice of the dancers when European stage dance was really muted for the history of stage dance. In Montpellier I spoke with dance historian Geneviève Vincent, and she said to me, "There were the witches, and the witches they were really using their voice". And then she said, "In baroque dance, people were talking to each other all the time while dancing". But if you ask me, the first stage dancer who used her voice in an interesting way was Valeska Gert. I realised throughout my research that in the 80s, somebody already published a lot about Valeska Gert. She was more famous in the France dance field than in Germany. In Germany she was much more forgotten, and she actually got picked up by the West German punk scene, who saw her in this very famous interview "Je später der Abend". And one year later, she died. My entrance point to Valeska Gert was not only because she's a very interesting person, who had an amazing life, but because wanted to write the history of the voice of dancers. And she was my fictional starting point. I made a piece about only her SoundDances (TonTänze). I decided to not talk about her private life, about her immigration, about how she was misunderstood, how she was an interdisciplinary artist. She was brilliant. And I decided to cut all of this out and to only talk about her voice. And I think by talking only about her voice, everything else is included in that. She also said it herself, "I am the first dancer who used her voice in dance".

Nitsan

For sure.

Jule

She talks about herself as if she's not in any community. But she fictionalised her own life, and that's what everybody does. I tried to understand something in my lecture-performance. In “I Intend to Sing” (2017) I reenact different sound dances, one from Valeska Gert Kummerlied, and Simone Forti's Throat Dance. I intend to sing lecture performances that came before Störlaut, before the Valeska Gert piece. And I also learned a score from Myriam Van Imschoot Scrambled Speech. Then I did Störlaut (2018) where I speculate about the sound dances of Valeska Gert, because some of them only have two sentences of description. But others I found in the archives as soundreels. So how, in a dance archive, can a sound reel play a role? There is a soundreel in the ADK in Berlin, and I went there, and they had this original sound reel.

There are also things I found that really repulse me and, and I try to be as honest as I can, knowing I'm the contemporary spectator. In German it's called “Sehgewohnheiten” – my habit of seeing what I am used to seeing. So it was very interesting for me to understand how my 21st century spectatorship is making me a

For sure.

Jule

She talks about herself as if she's not in any community. But she fictionalised her own life, and that's what everybody does. I tried to understand something in my lecture-performance. In “I Intend to Sing” (2017) I reenact different sound dances, one from Valeska Gert Kummerlied, and Simone Forti's Throat Dance. I intend to sing lecture performances that came before Störlaut, before the Valeska Gert piece. And I also learned a score from Myriam Van Imschoot Scrambled Speech. Then I did Störlaut (2018) where I speculate about the sound dances of Valeska Gert, because some of them only have two sentences of description. But others I found in the archives as soundreels. So how, in a dance archive, can a sound reel play a role? There is a soundreel in the ADK in Berlin, and I went there, and they had this original sound reel.

There are also things I found that really repulse me and, and I try to be as honest as I can, knowing I'm the contemporary spectator. In German it's called “Sehgewohnheiten” – my habit of seeing what I am used to seeing. So it was very interesting for me to understand how my 21st century spectatorship is making me a

Valeska Gert was more famous in the France dance field than in Germany, where she was much more forgotten, and she actually got picked up by the West German punk scene, who saw her in this very famous interview "Je später der Abend".

Nitsan

It seems to me that your work is refusing the contemporary... I haven't seen much, but it feels like you're kind of doubting "contemporary" in the work, because you're not letting people see something comfortable or even see something.

Jule

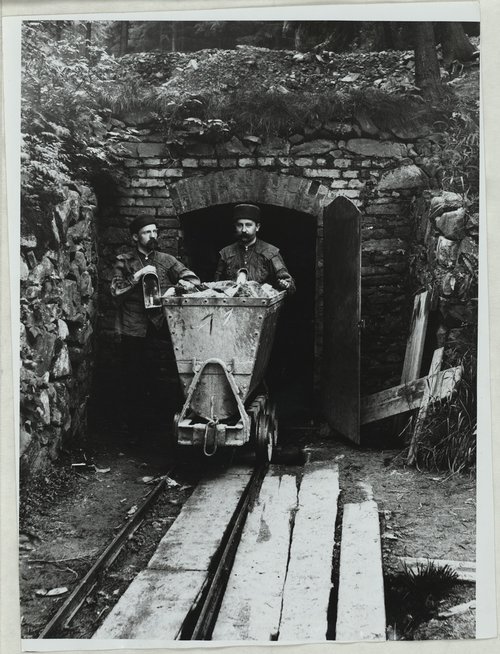

I have a lot of fun and I find a lot of humour in doing things that are absolutely anachronistic, for reasons that I find very contemporary. I do find my motivation is very contemporary, but I try to not give the aesthetic satisfaction. I identify my topics and my interests, and then I can stay happy with them. So the unsettling point is maybe to try to invite people to find allyships with topics or aesthetics that are not obvious. With Mars Dietz I did this piece called “Wismut- a nuclear choir” (2019) where we went to Chemnitz to make a research trip. It's about uranium mining in the Ore Mountains. We were learning mining folk dances, because in socialism, people had these funny folk dances where every job had their own dance. This is a very, very socialist aesthetic production basically to value the work, and so we learned some mining dances and they are so absurd. It's ridiculous from a contemporary perspective, but it's so nice if people work and have a dance group. So Wismut AG had its headquarters in Chemnitz, and they had their own dance group. People who were miners were dancing in their free time after work.

Nitsan

It kind of gives a light on why you're working with absurdity.

Jule

Well, history is also absurd.

Jule

I have a lot of fun and I find a lot of humour in doing things that are absolutely anachronistic, for reasons that I find very contemporary. I do find my motivation is very contemporary, but I try to not give the aesthetic satisfaction. I identify my topics and my interests, and then I can stay happy with them. So the unsettling point is maybe to try to invite people to find allyships with topics or aesthetics that are not obvious. With Mars Dietz I did this piece called “Wismut- a nuclear choir” (2019) where we went to Chemnitz to make a research trip. It's about uranium mining in the Ore Mountains. We were learning mining folk dances, because in socialism, people had these funny folk dances where every job had their own dance. This is a very, very socialist aesthetic production basically to value the work, and so we learned some mining dances and they are so absurd. It's ridiculous from a contemporary perspective, but it's so nice if people work and have a dance group. So Wismut AG had its headquarters in Chemnitz, and they had their own dance group. People who were miners were dancing in their free time after work.

Nitsan

It kind of gives a light on why you're working with absurdity.

Jule

Well, history is also absurd.

… what she did was unique and provocative. And then many people did it after her and now we see it as a cliche. But when she did it, it wasn't a cliche at all

Nitsan

Definitely everything is absurd. We are just trying to deny it in order to make meaning.

Definitely everything is absurd. We are just trying to deny it in order to make meaning.

Jule

We believe too much in sensemaking. I saw yesterday, this lecture by Arne Vogelgesang about QAnon that is actually a life role game that became reality. It's so horrible. How QAnon is basically coming out of a life role game format. And it's shaping reality and politics, you know, so how can we not say that history is absurd? It's not for laughing. But it's for knowing that the reasons why things happen are not based on rational thinking.

About the voice in dancing... I wanted to connect to people who do TonTanz now. So basically, Valeska Gert's definition really suited what I did before I even knew of her. That's why I started to make this no-budget-alternative programme From Breath to Matter in Kule (Kunsthaus KuLe Berlin), where people do TonTanz: fine artists, new music people, dance people. The historic speculation around it is if I claim "TonTanz exists", and I created a curation around it. It's completely without money – there's

… history is also absurd. <...> We believe too much in sensemaking.

Nitsan

It's almost to me like you're dealing with the dance field and not just with your work by doing that.

Sasha

I appreciate this strategic approach. Because from my experience, I feel that if we just fit existing infrastructure, we never do what is really important. So to question the existing institutions is one of the major purposes. Otherwise, we became just an entertaining market. I think that there is a demand in the art that audiences have, and only by questioning existing infrastructure we can answer this demand. Otherwise, it's something else.

Jule

It's really about how I can claim my practice for a temporality that is sustainable. I'm really lucky because this all started for me when I was 19. I found something that really resonated with me. It was a big accident. I guess I produced my own sense making process and I did not rely on institutionalized authorities so much.

Nitsan

I think it really does go with our question of, where does knowledge reside in your work? Or maybe we can even take out the word "work", but in your “efforts”. Is it the learning? Is it the change? Is it adapting? Is it refusing? Do we have to say "where it resides", because you're speaking about an embodied practice that you are giving voice to?

It's really about how I can claim my practice for a temporality that is sustainable. I'm really lucky because this all started for me when I was 19. I found something that really resonated with me. It was a big accident. I guess I produced my own sense making process and I did not rely on institutionalized authorities so much.

Nitsan

I think it really does go with our question of, where does knowledge reside in your work? Or maybe we can even take out the word "work", but in your “efforts”. Is it the learning? Is it the change? Is it adapting? Is it refusing? Do we have to say "where it resides", because you're speaking about an embodied practice that you are giving voice to?

… how I can claim my practice for a temporality that is sustainable?

Jule

So this thing I do in “Dissociation_Study” (2017) with the dissociating the image and the voice of the body from each other, really came from me feeling alienated with some of the things that I tried to do or tried to understand about the TonTänze of Valeska Gert. She always talks about the unity of the body and then I really had a dialogue with her about this, like, "Yeah, but this is in your time, when people are shocked about this, and I play in front of completely different people with different media experience". And in the Corona time, the media experiences are even more intense, because we're hyper mediated even more than before. But before the Corona crisis, I wanted to show that the body is not holistic and not one, but it's a lot of different "allys" as you called it. I tried to really understand what, for me, is the

the body is not holistic and not one, but it's a lot of different "allys" as you called it.

contemporary body that is dancing and vocalising. I needed this dissociation from the image and the voice. So this was really an answer to Valeska Gert; it's not a reenactment. She talks a lot about film, and how film in her time revolutionised this Sehgewohnheit, this habit of perception. And her dances are directly responding to this new medium of film. Sound film was so new and then comes this TonTanz – there's really something synchronized with them. And I think that the message, “You can't only trust what you see in a person” is a very important contemporary stance for me.

Nitsan

I heard this week on a movie, a choreographer said, "You can never really know what a dancer is thinking when they improvise". You can never really know what anyone thinks when they do anything. And that's what people tend to forget.

Nitsan

I heard this week on a movie, a choreographer said, "You can never really know what a dancer is thinking when they improvise". You can never really know what anyone thinks when they do anything. And that's what people tend to forget.

Jule

We seem to understand who people are just by them displaying themselves on the stage, but we don't. And this whole thing of unsettling that. We don't feel so comfortable with our claim of understanding what's going on. That's really important, and that has to do more with perception of bodies.

Sasha

Talking about this claim to clearly understand who they are, probably comes from the uncertainty of who we are. Is it clear for anyone? Who am I? And how could it be clearly fixed, and represented, and described?

Nitsan

Maybe it has to do with absoluteness and sensemaking in history? This capturing, that we are learning as we grow.

Jule

Genau. Yeah, there is something about that I never know. Because I see them. This opacity, basically, about knowing yourself or other people, that this stays active. We do not have full access to everything all the time, which I think is an illusion that is produced through certain cultural practices, actually.

Sasha

Since you worked a lot with Valeska Gert’s heritage, how do you think she would feel about the work that you have done from her work?

Jule

She, in my piece, definitely refuses certain things. And we have conflicts between us. When she writes in her works, she's really having very specific opinions. She has a very critical tone, and it's very beautiful. It was very nice for me to be in contact with her, and to stand her critique for my piece. And it's good to be critical, that we don't go to the archives and say, "I'm really happy with this work. This is really great. And I can feel very happy about this reconstruction that is not questioning". So I'm questioning her work, and I felt very aware of her questioning my work too. It's a very different relationship from what I have now with contemporary people who are alive. I learned a score from Antonia Baehr (My dog is my piano), I learned a piece from Myriam Van Imschoot (Scrambled speech), and I will learn a piece from Irena Tomažin (from Moved by Voice). It's a different thing, because we can have this meeting. And to create the speculative meeting with Valeska Gert's criticality, that was very interesting for me.

Sasha

It sounds like you really spent a beautiful time with her.

It sounds like you really spent a beautiful time with her.

I find a lot of humour in doing things that are absolutely anachronistic, for reasons that I find very contemporary.

Jule

I can talk about this, because I had much more time for this. And it resonates in the rest of the things that I did after too. This is a very specific relationship that goes beyond the piece that I did. We can really say that to spend time with something is such a privilege, and it doesn't happen so often.

Nitsan

I'm worried about TonTanz. I'm really curious, because it feels to me that what you're doing with TonTanz is a continuity of abrupted history. So would you be interested then in really trying to go into dance education systems and suggest this form of relating to dance?

I can talk about this, because I had much more time for this. And it resonates in the rest of the things that I did after too. This is a very specific relationship that goes beyond the piece that I did. We can really say that to spend time with something is such a privilege, and it doesn't happen so often.

Nitsan

I'm worried about TonTanz. I'm really curious, because it feels to me that what you're doing with TonTanz is a continuity of abrupted history. So would you be interested then in really trying to go into dance education systems and suggest this form of relating to dance?

Jule

My own dance education was very technical. And I'm now teaching a week in Amsterdam in ATD (Academy of Theatre and Dance) on a BA course. I experienced dance school as a place where I had to shut up, where I had no voice, and where I mostly needed to execute. And this was very triggering last week when I was teaching, because I felt that these students are educated to execute, and not to experience, and not to speak up, and so on. So that's why I did a lot of experiments with my voice. I practice a very specific somatic voice approach (Lichtenberger Methode) that deals with overtones, and with the anatomy of the larynx. And the desire to bring it very technically together was always there. Now, I teach voice for dancers and my main interest at the moment is to say voice and dance are two totally different things, and we first need to understand how different they are.. I think that what we really can learn is to listen more and to really understand. In the teaching I did last week, the first day we spent with the question, "Is the voice A body part or not?" I do think that this question of linking dance with voice is very paradoxical, and poses a lot of questions about how we dance. How do we work with dance in silence? How do we work with our nervous system? How do we work with musicality? How much is this instrument? We don't need to be loud all the time. We can also be silent as a rhetorical gesture, as a way of deciding what to do with that voice with that subjectivity.

Nitsan

I'm starting to think why questions need to be answered?

Jule

Exactly. They're just inspiring questions.

Nitsan

Questions to make more questions... The idea of the “answer”, I think, is Western. Asking questions is important practice.

I'm starting to think why questions need to be answered?

Jule

Exactly. They're just inspiring questions.

Nitsan

Questions to make more questions... The idea of the “answer”, I think, is Western. Asking questions is important practice.

"Is the voice a body part or not?"

I do think that this question of linking dance with voice is very paradoxical...

Sasha

What are the other extensions of our body that are not the limbs? And I'm thinking also about the gaze or the temperature? What else do we detach from our body that is related, but in a more complex way than we could articulate?

Jule

That's a challenge for perception. How can we make these things questionable for the audience in a performance? And also to not think that dance is what is happening at the edges of my body, at the visible edges of the body.

Nitsan

It throws me in too many places. We had a discussion earlier in the studio, I was saying that for me dance is searching for the best position. People are constantly searching for the best position, and this is the dance. And when they are settling, it's when they die, but they constantly search for the best position. It makes me think about the dance that is right now inside of my body, that's obviously there trying to pause, which is impossible. And I'm thinking about this multiplicity. And I'm thinking about the idea of refusing or disrupting the dance, or how do we even teach a technique to refuse and disrupt the dance? Because I think that's what dance students need the most. That is my position. And I think that this idea of the dancers’ voice is a political agency.

Jule

There's this essay from Anne Carson that is called the "Gender of Sound". And she shows how female voices in classical Greece were really only heard as noise. The whole precarity of gendered reading of a voice, which, of course can go much further than she was writing about in this essay. And my experience of teaching in different countries was that there was really something with female dancers’ voices that was very troubling for me. This is really crazy for me, if I think about the politics of the voice, even if you give feedback on how you speak, that's part of the politics of the voice, not just the performativity. It is about how different voices inhabit the space, and I tried to integrate this into the teaching that when they give feedback, when they say something, that this is part of the vocal practice.

And so part of this lecture-performance ”I intend to sing” was also silence as a rhetorical gesture, for example of refusing to participate in a language that you don't agree with. But of course, staying silent... well, it's not only passive, it's a huge pathway of where we find our voice. We can find our voice here, also. This can be my voice. But does my voice only become an activist voice a political voice when it's filled with language? It's really a question that I have. And I find it very hard to answer, because now in this From Breath to Matter in March, there's Edka Jarjab from Warsaw. She is a musician, fine artist, and activist who, in these demonstrations for the right to have abortions in Warsaw that are so extremely important, trains women to scream. She made a sound piece during the lockdown where individuals recorded demonstration slogans, and she edited them together and made a chorus piece. So she made a sonic demonstration of many bodies that couldn't gather because of the lockdown as a sound piece. People played it in their apartments and the police came, because it sounded as if there was a lot of people in the apartment and it's forbidden.

But actually, there's just one person playing the soundtrack. So this is also an activist voice. She found a form for a certain specific vocal gesture that is performative. But that is not based on argumentation as we know it from the activist side that is like Anklage (accusation – editors note). When you are taking a side,this is Anklage and this is what an activist would do. You would point out the injustice, say it, articulate it and hope then that something is changed. And that's extremely relevant. My question is, are there other activist vocal gestures from that?

But actually, there's just one person playing the soundtrack. So this is also an activist voice. She found a form for a certain specific vocal gesture that is performative. But that is not based on argumentation as we know it from the activist side that is like Anklage (accusation – editors note). When you are taking a side,this is Anklage and this is what an activist would do. You would point out the injustice, say it, articulate it and hope then that something is changed. And that's extremely relevant. My question is, are there other activist vocal gestures from that?

… some people's voices are only heard as noise.

Some people's voices will never reach the content, and that has to do with identity, with the gesture of speech, with racism, sexism, homophobia, with all of these things. Who can be heard?

Sasha

Just reminds me about a previous protest movement in Belarus before the one that is going on right now. People went out to stay in silence together, because everything was forbidden. They just came together on the square and just stayed in silence. And because of that they were attacked by police. They hadn’t done anything, but it was so loud that even people from the power structure system were able to hear this message. They recognised it.

Jule

Yeah, isn't that interesting? In Istanbul there was one choreographer that was always looking at an Atatürk statue. And then people were doing this in silence. And that's interesting in terms of voice, it doesn't need to be loud. But it's a gesture, a performative gesture. I find this a very good question. It's also much more of a paradox. Of course, I do think that everything has to go through rational argumentation is, because we have a lot of hate speech now and QAnon is the best example for vocal bullshit, basically. So we need rational argumentation, but I do think it's very important to understand how more people can participate and what history the norms of political speech have. Because there's this text from Rancière about democracy, and that some

people's voices are only heard as noise. Some people's voices will never reach the content, and that has to do with identity, with the gesture of speech, with racism, sexism, homophobia, with all of these things. Who can be heard? I feel that we need to search for a political voice. But we need to search for a political way of listening too. It is not only the actor who has to change a rhetorical gesture, it's also a question about how we listen and to whom we listen.

links:

Störlaut booklet

wismut- a nuclear choir- blog

dissociation study

Breathing Live

webpage

links:

Störlaut booklet

wismut- a nuclear choir- blog

dissociation study

Breathing Live

webpage

Moving Margins Chapter II

moving arti|facts from the margins of dance archives

into accessible scores and formats

Supported by the NATIONAL PERFORMANCE NETWORK

- STEPPING OUT, funded by the Federal Government

Commissioner for Culture and Media within the

framework of the initiative NEUSTART KULTUR.

Assistance Program for Dance.

artistic researches

Supported by the NATIONAL PERFORMANCE NETWORK

- STEPPING OUT, funded by the Federal Government

Commissioner for Culture and Media within the

framework of the initiative NEUSTART KULTUR.

Assistance Program for Dance.

© 2021 All rights reserved to Sasha Portyannikova, Nitsan Margaliot and the interviewees.