How spectators shape dance

and the city

Interview with Laurie Young

Edited by Nicole Bradbury

#archive #dance #memory #berlin #spectators #choreographers #embodied #body #oral #histories #berlin #theater #expertise #sensorium

Sasha

Laurie

I think, to go to the very beginning of how I became interested in archiving came from the fact that I would now be considered an older dancer, and I've also had the opportunity to stay with repertoire for many years. Now not so much, but until quite recently, I've been doing repertoire from 20 years ago, or 25 years ago and that's fairly unusual. At a certain point, I was asked to hand this information over. That's when I started thinking about my history with these pieces, my history as a performer, the idea that I become the archive of these movements, and how I then pass them on. So it came from aging, as a 47 year old, and having stuck with this repertoire for a very long time. Also, the choreographer that I used to work with for Sasha Waltz, she is also creating an archive of sorts. That sort of brought me to this place of remembrance, and brought me to a place of how do we pass on our information? How do we pass on an embodied knowledge? How do we share movement? What was the original context of how this movement was created? What will make this information useful for somebody else? And how can I do it not just with words, but through sharing in a studio, sharing a bodily practice in general, and then realizing how deep the movement lived in my body, after not doing a piece for 15 years? When suddenly, the music comes on, and I haven't thought about this piece for 15 years, and suddenly, I know it. Even if you don't want it in your body anymore, it's still there. So this incredible deep knowledge and this incredible body muscle memory that we all know, as dancers just became so evident, and realizing that I am a living archive. This thought extended then to how I would see dance in general.

"... since the fall of the wall, they've been seeing pretty much one dance show every other night, which means over 5,000 dance shows by 2015. Neither of them are dancers.

… they are these living archives of dance as spectators..."

… they are these living archives of dance as spectators..."

I thought I would talk a little bit about a piece that I did in 2015. So this couple, they are a husband and wife, and I've been looking at the back of their heads for 20 some years, because they have been at almost every dance show that I've seen. I struck up a conversation years and years ago when I saw them in 1997 at Sophiensaele watching “Allee der Kosmonauten” by Sasha Waltz and then I realized many many years later that they're still seeing shows. So I struck up a conversation with them and found out that actually since the fall of the wall, they've been seeing pretty much one dance show every other night, which means that they've seen over 5,000 dance shows by the time that we were making this piece together. Neither of them are dancers. They're not your typical dance audience, they're not artists, not choreographers. I realized that they are these living archives of dance as spectators, so I asked them if they would be interested in creating a piece together. My impetus was that we would ask them to recall their strongest memories of dance, That could be positive or negative, something that impacted them, something that's lasted. And then from those memories alone, we would try to recreate the pieces. Never going to the original primary source documentation, only using their memories as source material to recreate, coming from them as a living archive to reenactment and recreation. With their assistance we assembled a cast of five dancers, and they chose the dancers. Because they have been watching dance for so long, they have this incredible breadth of knowledge of different generations of dance. The dancers were Dieter Baumann, Joséphine Evrard, Chris Scherer, Martin Hansen and Ixchel Mendoza Hernández, we had quite a mixed cast that they chose, and together, we created these recreations from their memories. Andrea Keiz was also a key collaborator who worked closely with me during the entire process. She also brings with her a vast and in depth knowledge of Berlin dance history. So we had 11 pieces in the end. Some would last a minute, some would be fuller scenes.

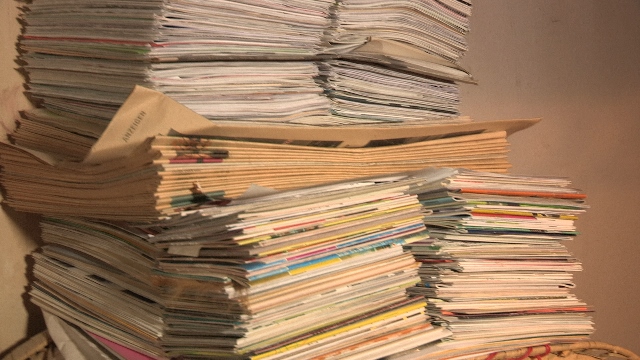

The process was quite amazing, first of all, because I had the privilege of being welcomed into their home, and realizing that they not only have seen thousands of live dance performances, but they've also collected everything. They have all the programs, they have all the ticket stubs. We all live with them. We live in their living room, we are their living room. It's incredible. So just realizing that it's not just the dance that they've collected, but the whole experience. The practice of dance watching entailed so much more than the performance. It was about the movements or the practice of going to the theater, of going back from the theater, how they etch out the

space based on dance spectating. It was quite touching to see their dedication and how they see everything, they really see everything. Then we had them in the studio, and suddenly they became choreographers, so they were choreographing their memories which is a really weird exercise to do, because memory- it mutates and changes. The more you think about it, the more it pulls away. What is memory, what is imagination, how do they live together? How do you grapple with that when you start to talk about that as an archive? So we found different strategies of how to work with memory and body memory. Then I became very interested in spectatorship as an archival process, so the spectator is becoming the archive specific to performance. So in the end, we created a piece, which presented different reenactments of their memories, but it was quite a challenging process.

I'm thinking about the idea of co-creation with them, but also with memories and it is such a particular way of reenactment. How were you feeling in facilitating that process of co-creating, because I think that there is something so certain when I hear music from a dance piece that I performed let's say 100 times over 10 years ago. I can do it in the middle of the night, but this is different, because they haven't danced those pieces. So there is something with a very strong memory regarding what they saw, but it's not an embodied memory, it is an embodied memory of what they saw. But it's not a muscular one, maybe it sits somewhere else in the body.

Laurie

What became really clear is that we don't share vocabulary, because they're not dancers. They don't have the dance vocabulary. As a process, first, they would send an email about images, or what they remember. For instance, something like hands in a group, hands clap clustering together. And they would try to describe to the dancers what it was, and then the dancers would try things out, and then it would kind of go back and forth. But like you said, they don't have the muscle memory, it's very frontal.

But I would suggest they do have their own muscle memory as spectators. Audience are not just passive recipients. They are co-creators through their co-presence. Spectators have bodies, too. Bodies that sense and perceive. They do embody dance through spectatorship.

But suddenly, the membrane between public and stage was broken and they became choreographers, though they wouldn’t consider themselves as choreographers in that moment. It was important for me that they didn't feel that pressure to do a correct replica of the original piece, it was really about their own subjective archive and memory. So there was no wrong and that was difficult to assuage sometimes, because I didn't want them to feel incorrect. Sometimes, there was this exciting moment where I would ask Jörg to demonstrate the movement instead of talking about it, then he became physical, and there's a moment when he comes to Josephine and

actually shows her how to lie down, so he actually became physical. That was super exciting. Then with Korinna, because she is disabled, she doesn't have the same kind of mobility which is also an important part of how they experienced dance. The way to the theatre for them is also very effortful. It takes hours for them to get to the theater. So Korinna would speak more and describe through language, and we also tried to encourage other ways. For instance, Heike Schuppelius built a maquette where we were trying not to always privilege language and speaking, but also tried to find other ways for her to think about her memory or to describe the memory. We created a maquette that was like a small scale theater, and she could have mannequins that she could move in space, so if she wasn't able to get on stage to move around, she could have another way of demonstrating. We tried to find strategies where you could facilitate their way of communicating, but because you're talking about memory, I didn't want to suggest too much. If I did, then suddenly the orange dress becomes red, and then it becomes green, so how to ask questions in a way that allows them to open up the field, but let them come to you with their memory and not try to pull it in a certain direction of my projection. That was very hard.

Sounds like psychotherapy, but in the best way it could be. And if we could continue, do you feel that this particular process enriched your artistic practice, in any way? Does it reside somewhere in your work?

Laurie

Completely. I think if I really take on this idea of spectatorship as archival practice, it changes a lot in terms of how I think of my relationship to the audience, as a performer and as a maker, but also to consider embodied archiving in general, and once you have that in your head, that it's kind of like choreography. This expanded sense of choreography is everywhere, and in that sense, for me, archival practice is potentially everywhere, or an embodied archival practice.

Nitsan

You mentioned that you continue relating to archives from this process onwards, and I wonder if you want to say what happened with our artistic work and investigation?

Laurie

There was another project that was actually before this one, which had me working in natural history museums, and working within archives of the Natural History Museum. This was a piece I made in 2011, called Natural Habitat, and I became busy with the cultural object of taxidermy animals, and working with the problematics of natural history museums. Things evolved, and I started collaborating with Susanne Schmitt, a sensory ethnographer. Through working with her, diving deeper into the archives of the Natural History Museum, part of our process was interviewing archivists and conservationists, but also museum guards, and the gatekeepers of these spaces. So I went from spectatorship as a cultural practice to exploring these very old archives and working in state archives, so very institutionalized spaces. We started thinking about not just the body as archive, but the body in the archive. How are archivists and researchers really influenced, or how are they allowed to move within these spaces? What is their somatic experience? There's all of these different parameters that they have to follow, because of conservation, or because of opening hours, or that it's not

There was another project that was actually before this one, which had me working in natural history museums, and working within archives of the Natural History Museum. This was a piece I made in 2011, called Natural Habitat, and I became busy with the cultural object of taxidermy animals, and working with the problematics of natural history museums. Things evolved, and I started collaborating with Susanne Schmitt, a sensory ethnographer. Through working with her, diving deeper into the archives of the Natural History Museum, part of our process was interviewing archivists and conservationists, but also museum guards, and the gatekeepers of these spaces. So I went from spectatorship as a cultural practice to exploring these very old archives and working in state archives, so very institutionalized spaces. We started thinking about not just the body as archive, but the body in the archive. How are archivists and researchers really influenced, or how are they allowed to move within these spaces? What is their somatic experience? There's all of these different parameters that they have to follow, because of conservation, or because of opening hours, or that it's not

Sasha

What is the position of your archive of inquiry regarding tradition? And technique? And did you follow that or oppose that in your work? And what are the concerns? For example, what is problematic about these archives? I think this is the major question that everyone who is entering work with heritage is facing. But maybe there is something specific about this archive of natural museums and also spectatorship, because I think it's not really on spot, the experience of spectatorship.

Laurie

I gravitate first towards the idea of spectatorship, because also now with COVID, it's such a question- who is spectating? It's not even happening, and for myself I’m leaning into my memories of dance, because I'm not seeing it live anymore. I think one of your questions is also what are the channels or transmissions, what is carrying in terms of information of this copresence? Spectatorship as an archival practice feels really relevant, because we need an audience for a performance to happen. I'm not sure that I have thought thoroughly about how spectatorship is problematic as an archive, but rather, I welcome the questions and then knowledge that spectators might bring after the liveness, and how the liveness is still active and will morph. So with the idea of literally a living archive, how does watching different movement really impact you? If I think of Korinna und Jörg, and I think about the 5000 shows that they've seen, and I think that they've seen an evolution of a roll on the floor, how does that live with them? How does that somehow, in perhaps subtle ways, shift their bodies? I'm not sure if that's an archival practice, but I feel like somehow it belongs inside that.

I gravitate first towards the idea of spectatorship, because also now with COVID, it's such a question- who is spectating? It's not even happening, and for myself I’m leaning into my memories of dance, because I'm not seeing it live anymore. I think one of your questions is also what are the channels or transmissions, what is carrying in terms of information of this copresence? Spectatorship as an archival practice feels really relevant, because we need an audience for a performance to happen. I'm not sure that I have thought thoroughly about how spectatorship is problematic as an archive, but rather, I welcome the questions and then knowledge that spectators might bring after the liveness, and how the liveness is still active and will morph. So with the idea of literally a living archive, how does watching different movement really impact you? If I think of Korinna und Jörg, and I think about the 5000 shows that they've seen, and I think that they've seen an evolution of a roll on the floor, how does that live with them? How does that somehow, in perhaps subtle ways, shift their bodies? I'm not sure if that's an archival practice, but I feel like somehow it belongs inside that.

Nitsan

Now that we are all in our homes, there is the archive of the every day, the studio, the home, they mix. What resonates with you? Maybe the professional, and the private, or public... even just a dance as something that happened in the studio, but is no longer happening there.

Laurie

I'm not sure how I can relate to an archive or an archival practice at the moment, other than the fact that, in the words of my good friend and collaborator, Justine A. Chambers where we also worked on an emergent and iconic archive of gestures of political resistance, she talks about the body as an “imperfect recording device”.

Everything that we're doing, or also the routine that we find ourselves in because of being in lockdown, these movements become repetitive and inscribed, become more recorded, become more part of our cellular makeup. Perhaps that is also a way of thinking about archive in this moment. I feel that if you think about repetitive moves in the same way, they become through the repetition meaningful, or even semantic, or turn into gestures. Maybe there's more of an inscription that becomes like a kind of time capsule. Because of this very particular time in history that we're in, I have to think about that.

Everything that we're doing...

these movements become repetitive and inscribed, become more recorded, become more part of our cellular makeup

these movements become repetitive and inscribed, become more recorded, become more part of our cellular makeup

Sasha

I am super fascinated by your work with spectatorship, and maybe we can consider in relation to that the community? Did this work change your perception? How did it influence the professional community that you work with? I was wondering about the process, and how dancers also embody the experience of working with spectators as the choreographers, because I think it's a very unique experience.

Laurie

I think, because I was working with the two of them, it's very specific. In terms of community, it was really about the Berlin dance community. All of the dance that they've experienced has been presented in Berlin. Obviously some were international, but at the same time very, very local. So then, in terms of community, this piece is really about the history of contemporary dance in Berlin over the last 25-30 years, because they were also bringing knowledge of not just dance, but where places used to exist, or theaters, even old bus routes, their whole movement practice of getting to and from the theater, the geography, this was all part of it. Dance festivals that no longer exist, because there's no longer that funding, it was a whole history and ecology of contemporary dance in Berlin through their very subjective eyes, but very informed. I contacted all of the choreographers whose pieces we were recreating, to let them know that this was going to happen. They were all invited to watch and to come to the show, and that felt very special, because they were perhaps people I wouldn't normally have had the opportunity to meet. This piece became this portal for many people. Multi generational, people who normally wouldn't work together were brought together because of this history. For me, that felt quite unique, and also then for them to be acknowledged as unique and important figures as spectators to dance. I mean, a lot of people in the Berlin contemporary dance community really recognize them, and I feel like perhaps their relationship to the dance community also changed through this process.

Sasha

Are they continuing this practice? I mean, not now during COVID, but they keep attending the performances?

Laurie

Oh yes, they will never stop this.

Nitsan

I think it's their survival practice perhaps. I remember seeing them always in the first row on the side?

Laurie

They always have an early entrance, and because of her mobility, they always have to have accessible seating which is also quite interesting, because they're always brought in 15 minutes before the show, so they also get to see dancers warming up. The time between pre show into the show, it's a very special perspective to have as a spectator, I think.

Are they continuing this practice? I mean, not now during COVID, but they keep attending the performances?

Laurie

Oh yes, they will never stop this.

Nitsan

I think it's their survival practice perhaps. I remember seeing them always in the first row on the side?

Laurie

They always have an early entrance, and because of her mobility, they always have to have accessible seating which is also quite interesting, because they're always brought in 15 minutes before the show, so they also get to see dancers warming up. The time between pre show into the show, it's a very special perspective to have as a spectator, I think.

Nitsan

I wonder if you would like to say a couple words about how you perceive the Berlin dance community, because we don't get to speak with so many dancers that also experience it from the dancer's perspective throughout those changes. Also, it seems like you have a very specific feeling for the term “embodied archive”.

Laurie

I feel very much on the outside of the Berlin dance community sometimes. But maybe I'm not the only one that feels that there are many communities, many, it’s not homogeneous and that's great. I think there's been a lot of really important work through Runder Tisch advocating for independent, freelance contemporary dance in Berlin, which is not often the case in other cities. The fact that there's such incredible advocacy to make space and resources available to dance is quite important. It's a lot of work and a lot of labor that people are doing without being paid I would imagine, but it's also indicative of this place, that dance needs to take up in the city, and should and already does, but it needs to be better resourced. I think that's quite unique to Berlin. I'm not sure you would find that in a lot of other places, and that's been exciting to sort of witness and also be a recipient of.

Embodied archiving is so hard to talk about and it's something I think about a lot, but I don't know how to answer it, because it's kind of everything. In the same way that choreography is everywhere, I don't really know how to distill it. Maybe it's about how one organizes it, this has already become part of my archive system. The intentionality of how you then access that information. I know that it is and I know that it's happening, and I know that it's happening in the present moment. But I don't really know how, and perhaps I only realize my access to this embodied archive as I call upon it. Maybe if you think of archiving as a collecting point that's then acknowledged for its information, then maybe it's about when it's called upon that I realize it's there.

… incredible advocacy to make space and resources available to dance is quite important <...> I think that's quite unique to Berlin.

Sometimes it seems to me that there is this natural resistance of embodied archive to be put into words.

Nitsan

And the vastness. Maybe there is something about capturing the vastness of artists that work with the body that are trying to put language on something that is such a resource compass, but at the same time a container.

Sasha

It’s a very nonlinear phenomenon. One of the core ideas of our project is the diversity of the Berlin scene, and how many people from different cultures are being presented and work in that scene, and the embodied archive that they carry with them, which creates such an interesting makeup. But there is a point that when we look at their archives, for example, there is a very particular lineage, which is kept as the history of contemporary dance. One of the points of this project is also to expand this narrative.

And the vastness. Maybe there is something about capturing the vastness of artists that work with the body that are trying to put language on something that is such a resource compass, but at the same time a container.

Sasha

It’s a very nonlinear phenomenon. One of the core ideas of our project is the diversity of the Berlin scene, and how many people from different cultures are being presented and work in that scene, and the embodied archive that they carry with them, which creates such an interesting makeup. But there is a point that when we look at their archives, for example, there is a very particular lineage, which is kept as the history of contemporary dance. One of the points of this project is also to expand this narrative.

Laurie

Absolutely. Who assembles these archives? Who is that voice of authority? Who was allowed in? Who is then represented? This idea of unauthorized histories, who authorizes this? Who is considered an expert? These gatekeepers? And yes, it's absolutely problematic, who gets to be in the canon? I refer back to Korinna und Jörg a lot, because this is also where I started thinking about these things. It really was this impulse and, they were selecting work from people that I had not known. I remember a critic coming to the show and she hated it, because none of her selections were part of their selections. Like they were undermining her expertise. It's absolutely crucial to how we get to experience, educate, and learn from, be in conversation with, and be in this sort of rhizomatic way of thinking. None of us have created work on our own, we're always entangled with our histories. How can we expand, also the sensorium of the archive, how can we have archives that call to different ways of receiving information, especially in dance? Who do we let in?

Absolutely. Who assembles these archives? Who is that voice of authority? Who was allowed in? Who is then represented? This idea of unauthorized histories, who authorizes this? Who is considered an expert? These gatekeepers? And yes, it's absolutely problematic, who gets to be in the canon? I refer back to Korinna und Jörg a lot, because this is also where I started thinking about these things. It really was this impulse and, they were selecting work from people that I had not known. I remember a critic coming to the show and she hated it, because none of her selections were part of their selections. Like they were undermining her expertise. It's absolutely crucial to how we get to experience, educate, and learn from, be in conversation with, and be in this sort of rhizomatic way of thinking. None of us have created work on our own, we're always entangled with our histories. How can we expand, also the sensorium of the archive, how can we have archives that call to different ways of receiving information, especially in dance? Who do we let in?

None of us have created work on our own, we're always entangled with our histories. How can we expand, also the sensorium of the archive, how can we have archives that call to different ways of receiving information, especially in dance? Who do we let in?

Nitsan

I find so many times we hear choreographers speaking about work and not dancers. I think what you're speaking about is really thinking about remembrance, and remembering untold stories, oral histories, and also the length of living. We also then speak about an ecology of a dancer's life almost, a dance piece, how much it lives, because if I dance it, maybe it's different than the amount of times you performed it through the years. A lot exists for me in oral histories, in transmission, and in who gets to transmit. Which voice is perceived as valuable as desirable?

Laurie

Yes, and who makes those decisions? Who's allowed to make those decisions? I think the idea of storytelling and oral history is really important to think about.

Sasha

How does the work from history help you to cope and face this very moment?

Laurie

It makes me weirdly nostalgic, and then, at the same time, I'm not looking at a lot of online dance right now... How do we move on from here? How can we learn from this moment of theatres being closed? I hope that it's not business as usual when we return, because the theater is certainly not a perfect place. If I can confront the past, which is a year ago, or three weeks ago, how do we return? I think it puts a lot of things in a different context. I think about theater in terms of accessibility and in terms of if we are to go back into the theater, how can we make it better? How can we make them more accessible? Yes, it's necessary, but why? It gets very existential very quickly, but I think some people talk about going back to a normal, but if we talk about going back to the theaters, the same architecture that we had before, with the knowledge that we have now, or that we're learning from, or how we've been having to experience dance in the last year, how can we apply that information and knowledge to make different theater? There's gotta be some seismic changes. It would be terrible if there weren't.

* photos by Laurie Young, Sebastian Bolesch, Arne Schmitt , stills from video by Andrea Keiz and video- trailer by TanzForum Berlin.

Moving Margins Chapter II

moving arti|facts from the margins of dance archives

into accessible scores and formats

Supported by the NATIONAL PERFORMANCE NETWORK

- STEPPING OUT, funded by the Federal Government

Commissioner for Culture and Media within the

framework of the initiative NEUSTART KULTUR.

Assistance Program for Dance.

artistic researches

Supported by the NATIONAL PERFORMANCE NETWORK

- STEPPING OUT, funded by the Federal Government

Commissioner for Culture and Media within the

framework of the initiative NEUSTART KULTUR.

Assistance Program for Dance.

© 2021 All rights reserved to Sasha Portyannikova, Nitsan Margaliot and the interviewees.